Citizen Meteor Science: Summary of the 2014 IMO Conference

Posted on Wed 24 September 2014 in meteors

I had the pleasure to take part in the International Meteor Conference this weekend, which is an annual meeting organised by the International Meteor Organisation (for which I am a council member). The IMO is an international non-profit organisation which exists to encourage international cooperation between amateur astronomers in the field of meteor science. Topics discussed include the observation of meteor showers using various methods, the modeling of the parent meteoroid streams, and the study of the occasional meteorite-dropping fireball events.

The study of these phenomena is limited to a large degree by our ability to monitor Earth's atmosphere across the globe in a continuous fashion. The field only counts about 100 full-time professionals worldwide, and hence amateur astronomers play a critical role in contributing and analysing the much-needed data. Out of the 130 participants that attend the meeting, roughly 10% are professional and 90% are amateur. Many of the amateurs carry out their work at a professional level, but are called amateurs simply because they are not being paid to do so.

Summarising the conference

I have been attending the conference for ten years now, and in fact helped to organise it twice (in 2005 and 2010). These meetings are important to me because they allowed me to gain experience in presenting and publishing scientific results when I was still an undergraduate student, and hence played an important role in enabling me to become an astronomer. They are also great fun because the participants actually love the subject ("amator" means "lover" after all). This implies that the participants tend to be driven entirely by curiosity, rather than the publication or funding pressure which makes so many professional academics behave in absurd ways (as per Darwin's theory of natural selection).

This year I was invited to present a conference summary as the last talk of the meeting. This means that, when all the sensible people went to bed on the last evening of the conference, I grabbed my laptop and summarised the meeting's 41 talks and 17 posters (which are all available on the conference website). I decided to approach this challenge by selecting one key slide from each of the speakers, and combining them into a coherent story.

The slides of my 20-minute summary are shown here (you can also download the PDF):

Of course the slides do not include the various comments I made, or the inevitable jokes, but they do offer a feeling for the contents of the meeting.

The orbit data revolution

The first thing I pointed out during the summary is that we are seeing a spectacular increase in the number of automated camera networks that operate to detect meteors. For example, during the meeting we learned that such networks are now extending beyond Europe, USA, Japan into e.g. Brazil and Morocco, thereby increasing our global view on the meteor activity. This is important because many meteor showers harbour young, compact dust trails that produce intense but short-lived outbursts, which last no longer than about 30 minutes. Such outbursts can only ever be observed from selected regions on Earth where both the geometry and the weather are right, and hence a global view is needed to record all the outbursts in a systematic way and ultimately chart the detailed structure of all the meteoroid streams.

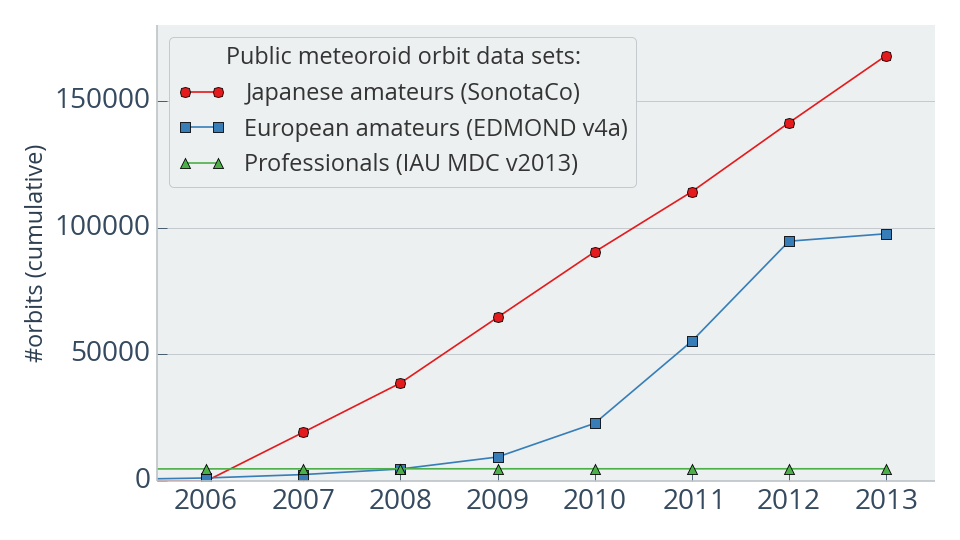

As well as recording more meteors, improvements in the data analysis software have led to a dramatic increase in the number of meteoroid orbits that are computed from those meteors (if observed simultaneously from multiple angles). I created the graph below, which shows the number of meteoroid orbits offered by the three most popular data sets that are publicly available: the SonotaCo Database (Japanese amateurs), the EDMOND Database (European amateurs), and the IAU Photographic Database (professionals). The graph illustrates that the number of observed meteoroid orbits has increased by nearly two orders of magnitude in just a couple of years.

Cumulative number of meteoroid orbits available in three popular public data sets. The number of orbits has increased from about 4,000 in 2006 to more than 250,000 in 2013. (Note that additional public data sets by amateurs exist, e.g. the Croatian Meteor Network catalogues.)

Why are meteors being recorded?

There are several good scientific reasons to obtain large statistical samples of meteors. These reasons include: (i) identifying new meteoroid streams, (ii) confirming the parameters of existing ones, (iii) testing dynamical models of their evolution, and (iv) computing the particle fluxes and mass distributions. Space agencies are particularly interested in the latter aspect, because meteoroids present an important hazard for spacecraft. The data are also of interest to the general public, indirectly, because they help predict when beautiful meteor shower displays will appear in the sky.

During my summary I reminded the audience that some of these science cases are better addressed using a small number of very accurate orbits, rather than the current large sets of somewhat noisy orbits. I drew a parallel between asteroid science, where the study of asteroid dynamics revolves largely around the famous inclination vs semi-major axis diagram, which reveals several asteroid families and the gravitational resonances that affect them. Models suggest that similar patterns exist in the population of meteoroids, but the accuracy of the observed orbits have so far proven insufficient to reveal such patterns in a routine way (see my previous talk on this topic).

Fortunately, several talks at the conference discussed ways in which the accuracy of the data can be improved. For example:

- Felix Bettonvil (Utrecht) and Auriane Egal (Paris) showed that a high-frequency electronic shutter can enable the accuracy of meteor velocities to be improved significantly, which in turn leads to better estimates for the semi-major axis (ie. the size of the orbit);

- Francois Colas (Paris) plans to include doppler shifts observed at radio frequencies to refine orbits determined from optical data;

- Pete Gural (Washington) reminded us that we would benefit from meteor surveys that exploit small telescopes rather than wide-angle camera lenses. In fact it is surprising that no such surveys seem to exist at present.

Visual data remains important

Although much of the recent increase in meteor data is brought about by sensitive video cameras, several speakers reminded us of the importance of visual (ie. human eye) and radio observations. Visual observations, in particular, remain the best method for estimating the fluxes of large meteoroids. This is because (i) video cameras do not nearly offer the same sensitivity and field of view as the human eye, and (ii) visual observations are well-understood and calibrated. Likewise, radio observations remain necessary to constrain the flux of smaller meteoroids.

The need for open data

I ended my summary with a rant on the importance of public data sets and open software. I believe that everyone in the field would benefit from having more groups share their data, for three key reasons:

- open data sets raise the profile of meteor science as a necessary branch of astrophysics -- the availability of high-quality databases may attract more researchers and resources into the field;

- there is ample evidence in other branches of astronomy that authors of open data sets receive more citations and the recognition of funding panels, because their openness allow other researchers to make serendipitous discoveries;

- last but not least, science needs to be reproducible!

During my rant I observed that, at present, many amateur meteor scientists share the data despite using their private money, whereas most professionals use public money yet keep the data private. A number of participants told me afterwards that this situation is quite shocking, really, and I share that feeling. I imagine that many professionals believe that keeping data private gives them an advantage over competing scientists, but what it really does -- in my humble opinion -- is that it makes the entire field of meteor science look like an outdated branch of astronomy that does not require researchers to analyse large contemporary data sets. Put differently, I asserted that the entire field is likely losing out on funding and scientific progress to other fields, because professional data sets aren't being shared.

The need for open software

I then went on to make similar observations about the habit of meteor scientists to keep their software closed. It seems rather obvious that open, re-usable software components can revolutionise the efficiency and accuracy of our observing projects. I pointed out that:

- as an author of open source software, you are free to choose your own license, eg. you can demand citations or require co-authorship if that is what you are worried about;

- authors of open source software do not have to offer support, it is perfectly fine to put source code on line with a disclaimer that you do not have the time to implement new features or fix bugs;

- we all have dirty code, so stop worrying about the quality -- if a piece of software is good enough to produce your scientific results, then by definition it is also good enough to share;

- papers on data analysis methods can never capture all the details, whereas source code can.

I then went on to explain how other branches of astrophysics are being made a lot easier by the existence of open source libraries such as AstroPy, which counts nearly 100 contributors and exploits modern tools such as GitHub to enable such mass collaboration. I asserted that we would all benefit from having a similar, more vibrant, meteor software community.

Although it is unlikely that many meteor workers will make a sudden shift towards open data and software, I do think that my brief and friendly rant may have inspired some. Let's wait and see!

Next year

We are very grateful to the FRIPON group for hosting this year's fabulous meeting. Next year's International Meteor Conference will take place in Austria on 27-30 August 2015. I can warmly recommend all those interested in meteors, at all levels, to join the fun!